Natural Rights and Politics in the Early Modern Period

Programme et présentation du colloque Natural Rights and Politics in the Early Modern Period qui se tient à la Scuola Superiore Meridionale (Université de Naples) les 2 et 3 Novembre 2023.

Despite the ubiquity of the idea of human rights in our political culture, and its strong presence in the work of political scientists, jurists and contemporary historians, scholarly interest in natural rights — the tradition from which human rights are drawn — remains sporadic and fragmentary. Natural rights were long considered the expression of a possessive and individualistic liberalism (C. B. Macpherson), born in tandem with capitalism and serving as its justification, or else as a nominalist aberration of Scholastic thought (Michel Villey). However, the pioneering work of medievalist Brian Tierney shows that subjective natural rights, seen as inhering in every individual in function of their humanity, go back at least as far as the 12th century. Far from being an expression of the omnipotence of the acquisitive will, natural rights were conceived of as limited by the principle of reciprocity. “Social” rights, such as the right to subsistence, are thus revealed to be not a late addition, but one of the first rights theorized by the medieval jurists of Bologna.

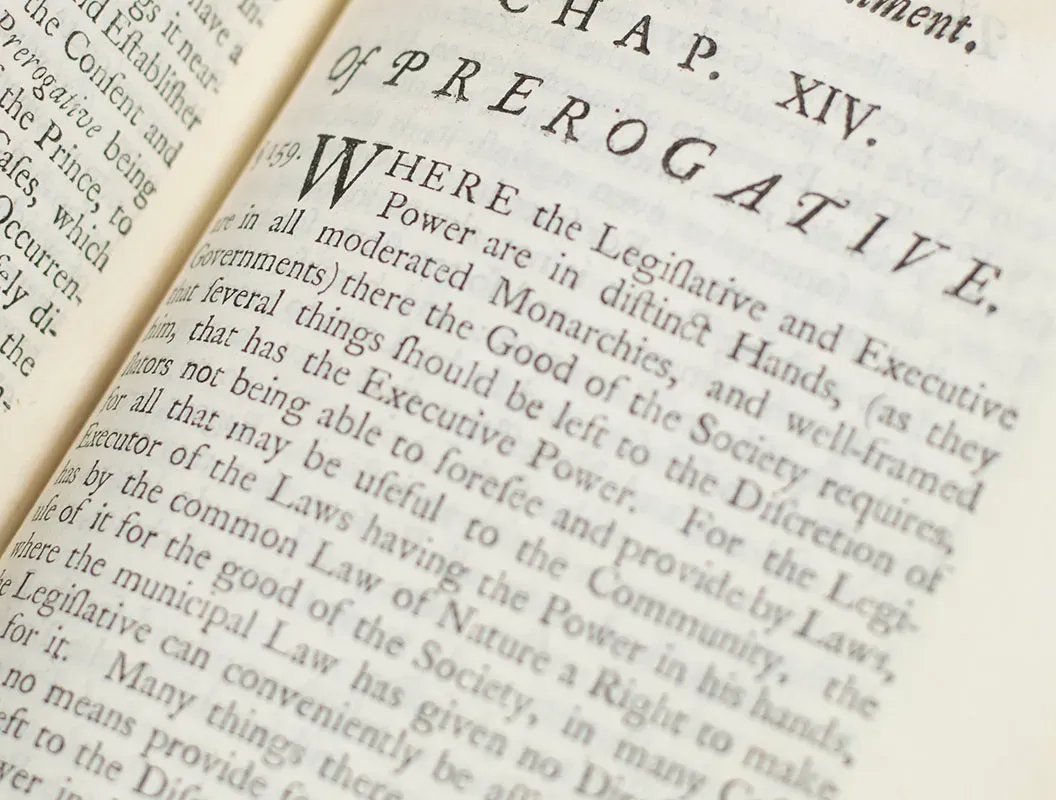

Although this tradition does present some diversity, certain 17th and 18th century authors, such as Thomas Hobbes or the physiocrats, represent real epistemological breaks with its basic principle, by introducing the idea of an unlimited right, whether that be the right of any individual in a state of nature, or that of landowners. However, these new conceptions — sometimes abusively conflated and often termed “liberal” or “modern” — did not replace older ideas of reciprocal rights, which continued to be highly influential.

Florence Gauthier has made apparent the connections between the natural rights of earlier periods and those of the “Age of Revolution(s)” of the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries. Within this continuity, a number of key sequences can be identified. Notably, as Vincenzo Ferrone has shown, the importance of the Enlightenment for the consolidation and diffusion of the doctrine of the natural “rights of man,” should not be underestimated. Following Gauthier’s Triomphe et mort du droit naturel en Révolution, there has been a renewed interest in the place of natural rights in the French Revolution and beyond, notably with the seminar “L’Esprit des Lumières et de la Révolution.” Rich debates have taken place and continue to flourish on natural rights in the thought of certain key theorists and actors, from the School of Salamanca to Thomas Paine, and a number of authors have studied the drafting of the English, American and French declarations of rights.

One important subject of controversy has been the supposed incompatibility of the natural rights tradition with what is often called classical republicanism. J. G. A. Pocock, one of the pioneers of the republican renewal in the historiography, has posited a classical republicanism characterized by positive liberty and in opposition to a liberalism which he identifies with natural rights and a negative conception of liberty. Another member of the Cambridge School, Quentin Skinner, has nonetheless made apparent that two forms of negative liberty could coexist in the Early Modern period: liberty as non-interference, but also liberty as non-domination (to use philosopher Philip Pettit’s terminology). If the law is a constraint on liberty according to the first, for the second, the law is, on the contrary, the only guarantee of liberty against arbitrary power. As Christopher Hamel and others have shown, this last conception was not incompatible with natural rights, and many Early Modern actors drew simultaneously from the republican and natural rights traditions.

The undeniable richness of many studies on natural rights in the Early Modern period does not prevent certain gaps in our present knowledge. Many debates, whether old or ongoing, also deserve to be revisited or deepened. For this reason, we are organizing a workshop on the deliberately broad subject of “Natural Rights and Politics in the Early Modern Period,” at the Scuola Superiore Meridionale in Naples on 2-3 November 2023.

This insistence on the relationship between natural rights and politics is intended not only to allow for the interrogation of natural rights as a theoretical political concept, but also and above all to excite interest in the various uses of concepts drawn from natural rights in precise political contexts. How did natural rights serve different political projects? How might evolving contexts have led to the evolution of conceptions of natural rights? To what debates did natural rights and the definition or interpretation of particular rights give rise, whether in moments of revolt or revolution or in apparently less turbulent contexts?

To that end, we propose three axes of reflection:

1) Natural rights and republicanism(s): If we allow that natural rights can be compatible with republicanism, or at least with some republicanisms, then a vast field of inquiry has only just been opened up on the articulations between the two, which vary by era, actors and contexts. We propose then to pursue the investigation launched by the 2008 journée d’étude “Républicanismes et droit naturel,” by inverting its terms: if a philosophy of natural rights can be republican, must it necessarily be so? And which republicanism(s) are at issue? Particular attention may be paid to the choice of vocabulary and to connected concepts such as liberty, equality, virtue or happiness, as well as to the political, socio-economic, cultural and religious contexts that inform the uses of these concepts.

2) The origin and evolution of particular rights: The enumeration of natural rights and of the social and political rights that may derive from them has never been obvious. Thus, we invite studies examining which rights emerged as significant in the course of the Early Modern Period, how they were theorized, included or not in any given declaration of rights, and how they were interpreted, as well as how those interpretations could evolve, in particular (but not exclusively) in revolutionary contexts. Some rights and chronologies have received more scholarly attention than others. One important example that has yet to sustain much interest is that of freedom of religion: how did it come to be seen (by some) as a natural right? What is the nature of the relationship between such a right and the concept of religious tolerance?

3) Concrete applications of natural rights: Finally, we invite studies of natural rights in the heart of events. How did different actors use natural rights to justify political policies? How did they interpret different rights while conceiving these policies and putting them into practice? To what debates did these different interpretations give rise as events were taking place? How might observers have interpreted revolts and revolutions by the metric of natural rights? The uses of natural rights in the American and French Revolutions have inspired the greatest number of studies, but many questions have not yet been fully explored even for these periods, while others also deserve investigation. What, for example, of the use of concepts of natural rights in various revolts which did not result in revolution? The issue of the natural right to subsistence was raised in the Flour War of 1775: was this an isolated case?

Scientific and Organizing Committee:

Marc BELISSA, Emeritus Professor of Early Modern History, MéMo, Université Paris Nanterre.

Yannick BOSC, Maître de conférences in Early Modern History, GRHis, Université de Rouen.

Christopher HAMEL, Maître de conférences in Philosophy, ERIAC, Université de Rouen.

Suzanne LEVIN, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Global History and Governance, Scuola Superiore Meridionale, Università degli Studi Federico II di Napoli.

Giulio TALINI, PhD Candidate, Global History and Governance, Scuola Superiore Meridionale, Università degli Studi Federico II di Napoli.

Alessandro TUCCILLO, Associate Professor of Early Modern History, CPS, Università degli Studi di Torino.