What Did “Terror is the Order of the Day” Mean in the French Revolution?

Par Suzanne Levin, Turin Humanities Programme, Fondazione 1563.

In recent years, debates about the “Terror” in the French Revolution have been enriched with several new perspectives. Despite this, the many works attempting to seek the “origins” of the “Terror” often take this inherited category for granted. Some scholars have nonetheless begun to interrogate or even deconstruct the “Terror”: Can we speak of the “Terror” as a unitary system, while recognizing its improvised and variable character?[1] Can we even evoke it as a straightforward reality, when it originated as a post-hoc ideological construct,[2] one meant moreover to discredit not only the violence and repression of 1793-1794, but also its democratic and social experimentation?[3] Might the continued usage of the chrononym “Terror” obscure more than it explains, reifying, among other myths, that of the French Revolution’s exceptionality?[4]

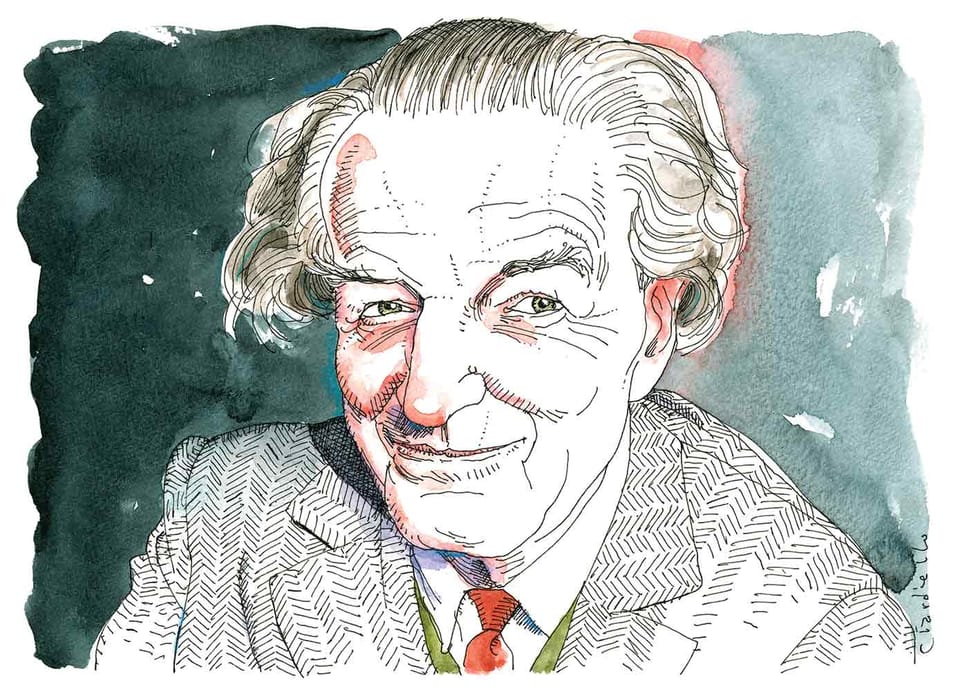

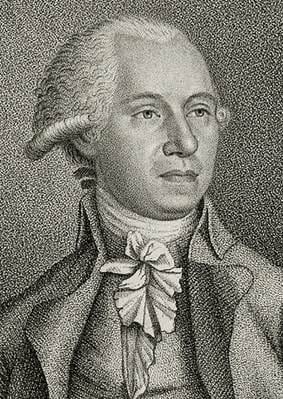

One approach that has proven fruitful in this reinterrogation of the “Terror,” has been to study how historical actors used the term “terror.”[5] The present article, drawn from my doctoral research on representative on mission and Committee of Public Safety member Pierre-Louis Prieur of the Marne, focuses on one overlooked aspect of these uses. The French National Convention never declared “terror” the “order of the day,” as Jean-Clément Martin has pointed out.[6] Yet, the phrase did gain traction with popular militants and was used by several representatives on mission sent from the Convention to the departments. Much attention has been paid to the “terror” portion of the phrase, but very little to the “order of the day.” What did it mean for terror to be order of the day? The example of Prieur of the Marne can help answer this question.